Saturable absorption

Saturable absorption is a property of materials where the absorption of light decreases with increasing light intensity. Most materials show some saturable absorption, but often only at very high optical intensities (close to the optical damage).

At sufficiently high incident light intensity, atoms in the ground state of a saturable absorber material become excited into an upper energy state at such a rate that there is insufficient time for them to decay back to the ground state before the ground state becomes depleted, and the absorption subsequently saturates.

Saturable absorbers are useful in laser cavities. The key parameters for a saturable absorber are its wavelength range (where it absorbs), its dynamic response (how fast it recovers), and its saturation intensity and fluence (at what intensity or pulse energy it saturates). They are commonly used for passive Q-switching.

Contents |

Phenomenology of saturable absorption

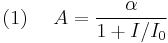

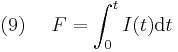

Within the simple model of saturated absorption, the relaxation rate of excitations does not depend on the intensity Then, for the continuous-wave operation, the absorption rate (or simply absorption)  is determined by intensity

is determined by intensity  :

:

where  is linear absorption, and

is linear absorption, and  is saturation intensity. These parameters are related with the concentration

is saturation intensity. These parameters are related with the concentration  of the active centers in the medium, the effective cross-sections

of the active centers in the medium, the effective cross-sections  and the lifetime

and the lifetime  of the excitations.[1]

of the excitations.[1]

Relation with Wright Omega function

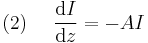

In the simplest geometry, when the rays of the absorbing light are parallel, the intensity can be described with the Bouguer law,

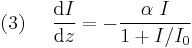

where  is coordinate in the direction of propagation. Substitution of (1) into (2) gives the equation

is coordinate in the direction of propagation. Substitution of (1) into (2) gives the equation

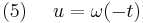

With the dimensionless variables  ,

,  , equation (3) can be rewritten as

, equation (3) can be rewritten as

The solution can be expressed in terms of the Wright Omega function  :

:

Relation with Lambert W function

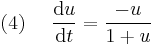

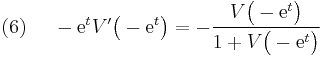

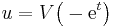

The solution can be expressed also through the related Lambert W function. Let  . Then

. Then

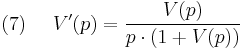

With new independent variable  , Equation (6) leads to the equation

, Equation (6) leads to the equation

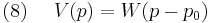

The formal solution can be written

where  is constant, but the equation

is constant, but the equation  may correspond to the non-physical value of intensity (intensity zero) or to the unusual branch of the Lambert W function.

may correspond to the non-physical value of intensity (intensity zero) or to the unusual branch of the Lambert W function.

Saturation fluence

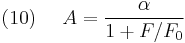

For pulsed operation, in the limiting case of short pulses, absorption can be expressed through the fluence

where time  should be small compared to the relaxation time of the medium; it is assumed that the intensity is zero at

should be small compared to the relaxation time of the medium; it is assumed that the intensity is zero at  . Then, the saturable absorption can be written as follows:

. Then, the saturable absorption can be written as follows:

where saturation fluence  is constant.

is constant.

In the intermediate case (neither cw, nor short pulse operation), the rate equations for excitation and relaxation in the optical medium must be considered together.

Saturation fluence is one of the factors that determine threshold in the gain media and limits the storage of energy in a pulsed disk laser.[2]

Mechanisms and examples of saturable absorption

Absorption saturation, which results in decreased absorption at high incident light intensity, competes with other mechanisms (for example, increase in temperature, formation of color centers, etc.), which result in increased absorption.[3][4] In particular, saturable absorption is only one of several mechanisms that produce self-pulsation in lasers, especially in semiconductor lasers.[5]

One atom thick layer of carbon, graphene, can be seen with the naked eye because it absorbs approximately 2.3% of white light, which is π times fine-structure constant.[6] The saturable absorption response of graphene is wavelength independent from UV to IR, mid-IR and even to THz frequencies.[7]

Saturable X-ray absorption

Saturable absorption has been demonstrated for X-rays. In one study, a thin 50 nanometres (2.0×10−6 in) foil of aluminium was irradiated with soft X-ray laser radiation (wavelength 13.5 nanometres (5.3×10−7 in)). The short laser pulse knocked out core L-shell electrons without breaking the crystalline structure of the metal, making it transparent to soft X-rays of the same wavelength for about 40 femtoseconds.[8][9]

See also

References

- ^ S. Colin; E. Contesse, P. Le Boudec, G. Stephan, and F. Sanchez (1996). "Evidence of a saturable-absorption effect in heavily erbium-doped fibers". Optics Letters 21 (24): 1987–1989. Bibcode 1996OptL...21.1987C. doi:10.1364/OL.21.001987. PMID 19881868.

- ^ D.Kouznetsov. (2008). "Storage of energy in disk-shaped laser materials". Research Letters in Physics 2008: Article ID 717414. Bibcode 2008RLPhy2008E..17K. doi:10.1155/2008/717414.

- ^ J.Koponen; M.Söderlund, H.J.Hoffman, D.Kliner, J.Koplow,J.L.Archambault, L.Reekie, P.St.J.Russell, and D.N.Payne (2007). "Photodarkening measurements in large mode area fibers". Proceedings of SPIE 6553 (5): 783–9. doi:10.1117/12.712545. PMID 17645476.

- ^ L. Dong; J. L. Archambault, L. Reekie, P. St. J. Russell, and D. N. Payne (1995). "Photoinduced absorption change in germanosilicate preforms: evidence for the color-center model of photosensitivity". Applied Optics 34 (18): 3436–40. Bibcode 1995ApOpt..34.3436D. doi:10.1364/AO.34.003436. PMID 21052157.

- ^ Thomas L. Paoli (1979). "Saturable absorption effects in the self-pulsing (AlGa)As junction laser". Appl.Phys.Lett. 34 (10): 652. Bibcode 1979ApPhL..34..652P. doi:10.1063/1.90625.

- ^ Kuzmenko, A. B.; van Heumen, E.; Carbone, F.; van der Marel, D. (2008). "Universal infrared conductance of graphite". Phys Rev Lett 100 (11): 117401. Bibcode 2008PhRvL.100k7401K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.117401. PMID 18517825.

- ^ Zhang, H. et al., (2010). "Graphene mode locked, wavelength-tunable, dissipative soliton fiber laser". Applied Physics Letters 96 (11): 111112. arXiv:1003.0154. Bibcode 2010ApPhL..96k1112Z. doi:10.1063/1.3367743. http://www.sciencenet.cn/upload/blog/file/2010/3/20103191224576536.pdf.

- ^ "Transparent Aluminum Is ‘New State Of Matter’". sciencedaily.com. July 27, 2009. http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/07/090727130814.htm. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ^ Nagler, Bob; Zastrau, Ulf; Fustlin, Roland R.; Vinko, Sam M.; Whitcher, Thomas; Nelson, A. J.; Sobierajski, Ryszard; Krzywinski, Jacek et al. (2009). "Turning solid aluminium transparent by intense soft X-ray photoionization". Nature Physics 5 (9): 693. Bibcode 2009NatPh...5..693B. doi:10.1038/nphys1341.